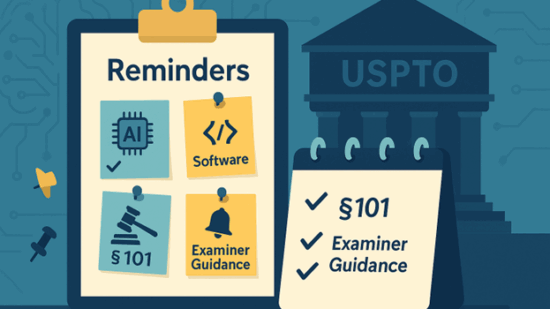

In our earlier posts, we discussed the significance of Ex Parte Desjardins: first when the Appeals Review Panel vacated the § 101 rejection, and again when Director Squires designated the decision as precedential.

Today, the USPTO has taken the next step: it has formally issued a memo to the examining corps announcing updates to the MPEP that incorporate Desjardins directly into the Office’s subject-matter eligibility framework.

Continue Reading Further Update: USPTO Issues Memo Integrating Desjardins Into the MPEP